Venezuela: Can “Bolivarian Revolution” continue?

The death of President Hugo Chavez on March 5 led many to question whether the “Bolivarian Revolution” of significant social and economic changes could continue without Chavez’s larger-than-life presence.

The following article appeared in the May-June 2013 issue of NewsNotes.

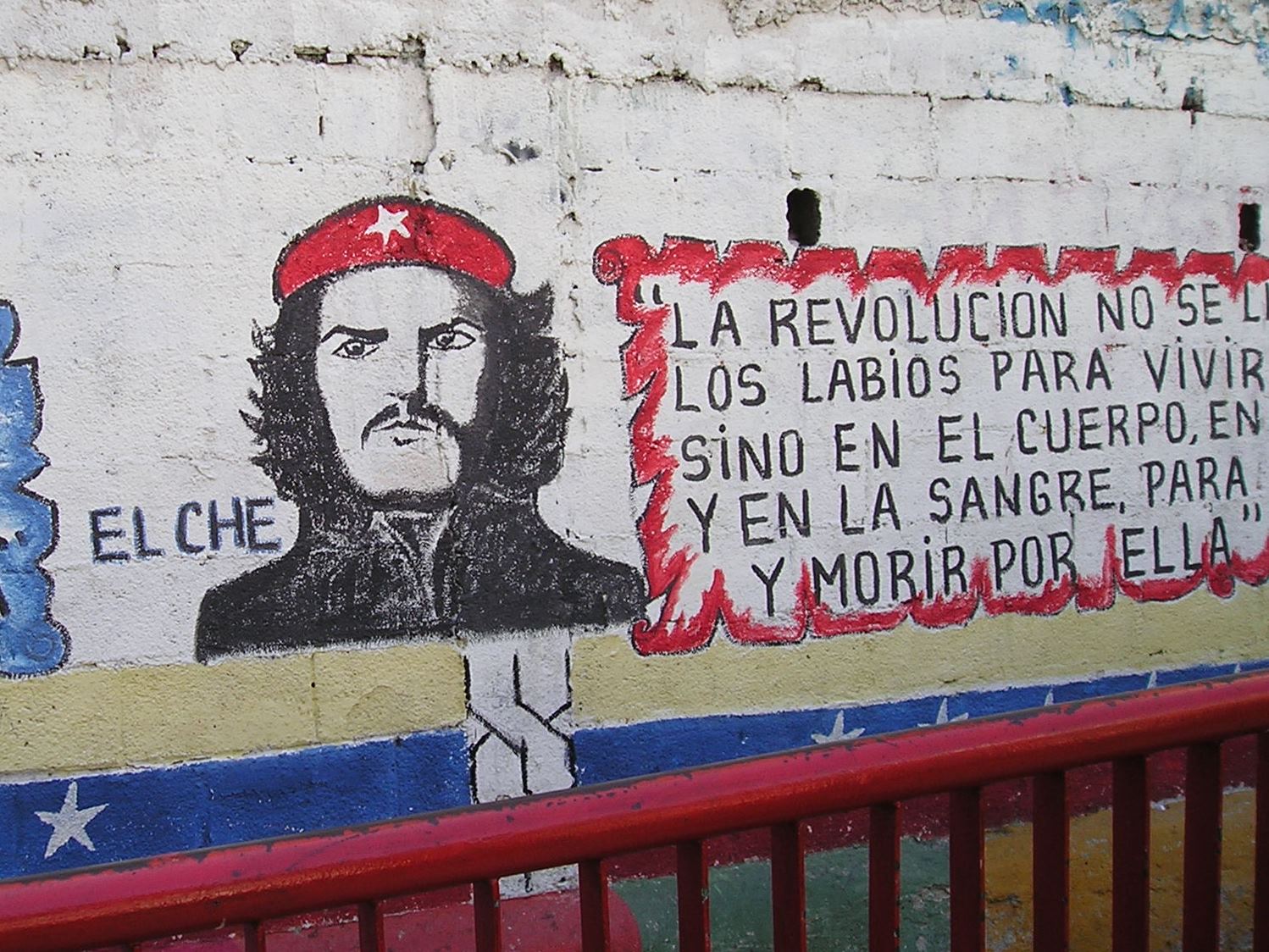

Photo of graffiti in Caracas; the quote from Che Guevara is translated: “The revolution is not to be carried on the lips to live off it, but in the heart to die for it.”

The death of President Hugo Chavez on March 5 led many to question whether the “Bolivarian Revolution” of significant social and economic changes could continue without Chavez’s larger-than-life presence. Hoping to return to power after 14 years as the main opposition coalition, the Democratic Unity Roundtable chose state governor Henrique Carilles to run against Chavez’s vice president Nicolas Maduro in the presidential election on April 14. After the hurried but energetic campaign, Maduro won by a narrow margin (50.8 percent to 49.0 percent), a result that led Carilles to call for a recount of all ballot boxes even though 53 percent of them had already been verified through Venezuela’s electoral system. While the National Electoral Council has declared Maduro to be president and political leaders from around the world have congratulated him on being elected, the Obama administration refuses (as of this writing) to acknowledge the results. Judging from the administration’s reaction to the elections and statements by new Secretary of State John Kerry it appears likely that relations between the two countries will not improve nor worsen. But if Maduro is able to continue improving the lives of Venezuelans and unite Latin American countries while addressing pressing problems with violence and economic imbalances, it is possible that the Bolivarian Revolution could continue for many years.

U.S. media coverage of the elections were consistently one-sided, presenting only negative information about Venezuela while ignoring significant positive changes that have occurred there in the last decade. USA Today perhaps best represented this imbalanced reporting, describing Chavez’s presidency as having “left Venezuela with high unemployment, soaring inflation, food shortages and falling petroleum production in a country with the world’s highest proven oil reserves. Its $30 billion fiscal deficit is equal to about 10 percent of the country’s gross domestic product.”

While these are some problems facing Venezuela today they are hardly crises with unemployment more than six percent lower than when Chavez became president (eight percent in 2012 vs. 14.5 percent in 1998) and inflation much lower than in the 1990s. While overblowing Venezuela’s problems, USA Today and most other mainstream sources failed to show any positive news such as the facts that since 2004 poverty in the country was cut in half, extreme poverty fell by 70 percent, and real per capita income grew by almost 2.5 percent annually. Over the last eight years, inequality fell sharply, illiteracy was eradicated, and millions of Venezuelans with lower incomes have much better access to health care and education (one in three Venezuelans is currently enrolled in high school or university). Infant mortality in Venezuela has been reduced from 21 per 1,000 babies to 13, the third lowest rate in South America. As the Center for Economic Policy Research’s Mark Weisbrot points out, “these numbers are not in dispute among economists or other experts, nor among international agencies such as the World Bank, IMF or United Nations. But they are rarely reported in the major Western media.”

Indeed, to listen to most U.S. media, one could wonder how Chavez and his political allies were so popular as to win 15 of the last 16 elections in the country. But Latinobarometro, an in-depth annual survey of Latin Americans on issues such has democracy, trust in government, economic outlook, etc., has consistently shown that Venezuelans during Chavez’s presidency are more likely to believe that their government is democratic and “governs for the majority” than people in most neighboring countries.

The U.S. decision to not accept the election results has not helped in any way. Venezuela is recognized worldwide for its high quality electoral system with Jimmy Carter describing it as the best in the world. Votes are made and stored on touch screen computers, then printed out, verified by the voter and deposited in urns. Immediately after the vote, 53 percent of urns, chosen randomly, are recounted to verify that the printed votes are the same as those recorded on the computer making the system as very resistant to fraud. This is done even though a simpler three to four percent recount would be enough to statistically verify the results.

Despite knowing this, the Obama administration has held out recognition of Maduro’s victory until 100 percent of the urns are recounted. This is the opposite reaction that the U.S. had with an even closer election in 2006 in Mexico, a country with a much less sophisticated voting system than Venezuela. There, when Felipe Calderon won by only 0.2 percent amid much more serious charges of fraud, President Bush quickly called to confirm Calderon’s “victory” and carried out an international campaign to convince other countries to recognize his presidency.

It is highly unlikely that the recount of the remaining 47 percent of urns will change the result. One economist estimated that chance to be about one in 25 thousand trillion. But by refusing to acknowledge Maduro’s victory, the U.S. has given extra energy to the opposition’s intractability, leading violent protests resulting in at least seven deaths. Perhaps this is foreshadowing of the difficulties Maduro will face, similar to what Chavez faced in his first six years as president when the U.S.-supported opposition repeatedly refused to accept election results, and carried out a short-lived coup in 2002 and worker lockout by oil company executives in 2002-2003 that decimated the Venezuelan economy.

Originally the Spanish government and Jose Miguel Insulza, Secretary General of the Organization of American States (but not the OAS as an organization) were the only others to join the U.S. in not recognizing Maduro’s victory, but now even those two holdouts have ceded that Maduro is the legitimate president of Venezuela, leaving the U.S. completely isolated once again in its resistance to Venezuelan democracy.

The close election results show how important Chavez’s personal charisma was in bringing in votes. Maduro, with a much quieter and reserved personality, has not been able to solidify the same amount of support either within Chavez’s party, the PSUV, or with swing voters. It will be important that he deal fairly and transparently with the opposition while addressing growing inflation and worsening violence. Judging from the shifts Maduro has made in his Cabinet, these two issues will be the special foci of the government. Perhaps the bigger question is whether the U.S. and members of Venezuela’s opposition will allow the Maduro government to function or will again resort to sabotage and other means to undermine it.